Christiaan Triebert describes himself as a digital forensics researcher. While he’s reported from locations around the world, he’s best known for his investigative and award-winning use of open source information: videos, images, data and information publicly available online that, if found, verified and provided with adequate context can tell important stories and challenge powerful narratives.

Having followed Christiaan and Bellingcat’s work — particularly their investigations into events in the Arab world — last week I had the opportunity to interview Christiaan about his work.

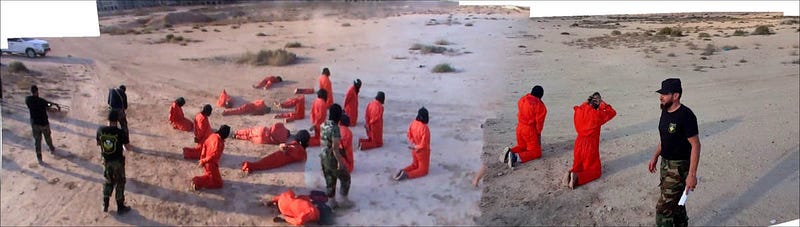

In August 2017, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued its first ever arrest warrant solely based on social media evidence. The arrest warrant accuses Mahmoud Mustafa Busayf Al-Werfalli (hereafter referred to as ‘Werfalli’), an alleged commander of the Al-Saiqa Brigade of the Libyan National Army (LNA), of mass executions in or near Benghazi.”

— Christiaan Triebert- Geolocating Libya’s Social Media Executioner

Do you think we will see more warrants based on social media evidence?

We are going to see an increase in this kind of arrest warrant. There’s so much information out there that could be potential evidence in legal cases. We have seen European courts, especially Swedish courts, are using social media footage in trials.

On the other hand there are also some obstacles: YouTube, Facebook and Twitter have been removing content. While they have valid reasons to remove certain images and videos that may contain violence or may spread propaganda, they are also potentially removing footage that may be used as evidence in legal cases.

Bellingcat is supported by Google’s Digital News Initiative and through those contacts we are trying to set up a discussion about the issue of YouTube content takedowns. In the meantime it is good to have tools like Check that archive our investigations.

Bellingcat is starting using Keep on Check to archive videos and saving their important work from social media network removing.

To what extent can evidence from social media be used in a legal case?

If we look at the case of the MH17 [a Malaysia Airlines passenger flight shot down over Eastern Ukraine in 2014, one of Bellingcat’s major investigations] from the social media evidence and open source information evidence that Bellingcat collected, we can basically prove who provided the weapon that shot down the airplane, but this is as far as it goes. It doesn’t prove or uncover who actually pressed the button. This is something which is very hard to confirm or deny, but open source investigation can definitely provide context and maybe more.

Why Libya?

Eliot [Higgins, founder of Bellingcat] was looking at Libya before he even founded Bellingcat, then all the attention shifted to Syria. Indeed the ICC warrant, which is solely based on social media evidence, is a very significant development in the history of ICC. Because we are always using this opens source material, it was a very interesting case for us to see: can we verify the location, verify the time, can we verify the dates of these executions? Our main question was can we do what we usually do in investigating conflict with the content referenced in this ICC warrant? Can we verify the social media evidence they are presenting? it was very interesting to see an international legal body is using the same kind of material that we use day to day at work, and we used Check to verify.

How did Check help you write this story?

The ICC referred to the upload dates and description of the videos on Facebook, so it wasn’t hard to find them online. We weren’t able to geolocate all of the videos, because some of them are very hard to geolocate. We are still searching for visual clues, but we did manage to geolocate several of them. A visual clue can be anything, like a building, a tree, a dirt track, an orchard, an electricity pylon — every kind of visual aspect you can see in the video, we can use as clues to geolocate.

For example, based on the electricity pylon visible in one video, people were looking at the electricity network in Benghazi to see where such electricity pylons exist. That’s just one way to find the exact location.

Once we figured out the exact location, we started using more recent Satellite imagery to work out the date. This was a very macabre example, because we found blood stains visible at the location, in satellite image after the executions. This also shows us how high resolution modern satellite imagery is. After we have the exact location, we can use SunCalc and the direction and length of shadows to estimate time of these videos.

You work on content from Syria, Turkey, Libya, Ukraine: Is language a barrier for crowdsourcing? Do you need to translate your work in Arabic?

I can read and write Arabic, and Bellingcat is very much a collective. We have Arabic speakers of different dialects in our community. It would be great for Bellingcat to get funds to translate our investigations that we are doing into Arabic, especially if we are talking about a crowd-sourcing campaign. We need to publish in Arabic so we can establish our community, and get more people to know how to do this type of investigation.

Crowd source campaign: #StopChildAbuse

“The most innocent clues can sometimes help crack a case. The objects are all taken from the background of an image with sexually explicit material involving minors. For all images below, every other investigative avenue has already been examined. Therefore we are requesting your assistance in identifying the origin of some of these objects. We are convinced that more eyes will lead to more leads and will ultimately help to save these children.”

– Christiaan Triebert– Stop Child Abuse: Trace an Object

How do you use Check for crowd-sourcing? What’s your basic checklist?

Everyone can support #StopChildAbuse campaign. Check was the best platform for it, because we can invite people to identify and we have found a lot of objects. It’s a great case for how strong crowd-sourcing can be: this is the European police (EuroPol) asking the crowd for help, and it has been very successful.

We have been using Check for a long time. The work of Bellingcat is built on the power of crowdsourcing, and when we are investigating Russian airstrikes or MH17 we use Check to build and geolocate a database of relevant content.

Our community is growing and with new features from Check, it’s the best tool to organize this crowd-sourcing campaign. It’s really giving power to the crowd.

How did you get interested in open source investigation?

When I was still in school I used to look at maps, and I wanted to travel the world. Then I worked as a freelance journalist and I started traveling and working more in conflict zones.

What I noticed from being on the ground in Iraq, on the front lines, is that sometimes I can find more information on the internet about an airstrike than information from actually being there. I’m not saying that being on the ground isn’t important for a journalist, it’s very important. In 2015 I started working with Bellingcat, and since then I have been working day in and day out on investigations covering everything from airstrikes in Syria to illegal mining in Colombia. Now we are searching for new topics to investigate: there’s a lot left to uncover with open source investigation.

What are you currently working on?

A while ago, I was on Dutch TV talking about investigation and there was 11 year-old boy who saw me on TV and he wanted to interview me for primary school project. We talked for many hours and by the end Manu told me: you use all these cool tools and methods to investigate war and conflict, I want to use these tools to investigate something that I care about: animals and nature. I saw myself in him, and I wanted to protect wildlife, so we started working on Manu’s Shark Finning Project for Primary School and this is one exciting thing I’m working on.